http://www.artpapers.org/feature_articles/article1.htm

AFTER THE CULTURE WARS

Censorship works best when no one knows it’s happening

By Richard Meyer

Last January, the White House dispatched Laura Bush to announce a proposed eighteen million dollar increase to the budget of the National Endowment for the Arts, the agency’s largest boost in over twenty years. However, there’s a catch: almost all of the funds are reserved for an initiative entitled “American Masterpieces: Three Centuries of Artistic Genius,” an exhibition of art, dance, music and theater to tour all fifty states, including small towns and military bases, over three years. “Through American Masterpieces,” Mrs. Bush affirmed, “citizens will reconnect with our Nation’s great artistic achievement and rich cultural heritage.” The First Lady furnished no details about what the show would include but, as a columnist in the San Francisco Chronicle wryly noted, “It’s a safe bet Piss Christ won’t be featured.”

In the fifteen years since Andres Serrano’s photograph of a plastic crucifix in a luminous bath of urine inaugurated the culture wars over federally funded art, the NEA has retreated ever further from its founding mission of supporting living artists, including, most saliently, terminating all grants to visual artists, museum professionals, choreographers, composers and solo performers. Moreover, the NEA now must consider what officials call “general standards of decency” when awarding grants to art exhibitions and institutions—decency in this context precluding anything sexually suggestive or politically sensitive. Faced with repeated calls for its dismantling throughout the 1990s, the NEA crafted a survival strategy that severs it from potentially controversial art. And the strategy seems to have succeeded. No one protests the NEA anymore or expects the federal government to support socially critical or politically outspoken artists.

With the NEA now promoting a sanitized vision of American art, artists whose work deviates from that vision face the threat of censorship. The effects of the culture wars persist, though in ways that most often remain unspoken or not consciously recognized. In what follows, I examine three instances in which contemporary artists have been subjected to public attacks and censorship campaigns. None of the cases provoked a national controversy like that which erupted over the photographs of Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe in 1989, partly because none of the artists received NEA funding. Public visibility does not, however, accurately measure censorship’s effectiveness. In fact, censorship may be most powerful when it is least palpable, when virtually no one knows that it has even occurred.

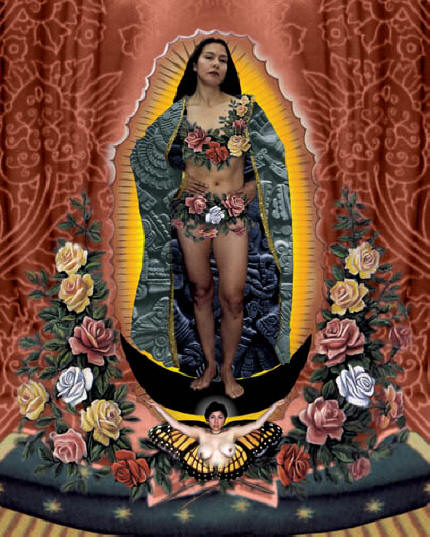

Our Lady

Alma Lopez, Our Lady, 1999, iris print on canvas, 14 by 17 inches (courtesy the artist).

The exhibit “Cyber Arte: Where Tradition Meets Technology” opened at Santa Fe’s Museum of International Folk Art in February 2001. The show, which traced the intersection of folk imagery and digital technologies in the work of four Latina artists, included Our Lady, a digital collage by Alma Lopez that reworks the traditional iconography of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Shortly after the opening, the Catholic Church publicly reviled Lopez while the curator of the exhibition, Tey Marianna Nunn, received death threats and state lawmakers threatened to pull government funding from the museum unless it removed the offending work. The Archbishop of Santa Fe, Michael J. Sheehan, characterized Our Lady as “repulsive, insulting, even sacrilegious...Here is the mother of God depicted like a tart or a call girl. The image of Mary depicted in this way has no place in a publicly supported museum.”

The vehement response to Lopez’ work stemmed in large part from the status of the Virgin of Guadalupe as a beloved, nearly ubiquitous figure in Mexican-American Catholicism.1 More than thirty churches in New Mexico alone are dedicated to her. The Virgin of Guadalupe’s image has been reworked countless times in candles, curios, paintings, sculptural figurines, t-shirts, jewelry, pillow cases, clocks, handkerchiefs, car ornaments, matchbox covers and sundry other objects. Notwithstanding this figure’s virtually limitless reproducibility in secular and sacred contexts, Lopez’ revision of our lady seemed blasphemous and indecent. In place of the demure virgin with down-turned head, Lopez offers a physically confident Latina, hands planted firmly on her waist rather than joined in a gesture of worship. Rather than being covered in head to toe drapery, Lopez’s virgin wears only two garlands of roses beneath her open robe, now resplendently flocked with ancient Aztec imagery.2

Although Lopez sought an updated but still beatified Virgin in Our Lady, its detractors saw just the opposite. Jose Villegas, a Catholic parishioner who helped spearhead the protest against Our Lady, said, “I see the devil, I don’t see our Blessed Mother. I’m 42 years old and I never have and never will see her in a bikini.”3

However, the local controversy around the “Madonna in a bikini” overlooked the bare-breasted woman whom Lopez had inserted beneath the Virgin in lieu of the traditional clothed male angel. The homoerotic suggestion of the angel/virgin coupling in Our Lady is made explicit in Lopez’ earlier collage

Lupe and Sirena in Love. In that work, the virgin appears in traditional guise, fully garbed, her head modestly turned down, but with her left hand cupping La Sirena’s exposed breast while her right hand rests on the mermaid’s fishy, iridescent bottom.

Gay and lesbian artists respond in many ways to the public attacks and censorship campaigns directed against their work, negotiating situations in which their work is sensationalized, distorted and denounced even as it is reproduced and recirculated under the sign of scandal. Lopez’ strategy was to create an Internet archive of everything related to the “Our Lady” controversy—e-mail exchanges, newspaper articles, letters of support, hate mail—thus moving the controversy out of Santa Fe to the virtual space of the World Wide Web, whence this digital collage came.

John Trobaugh, Meeting Mr. Wright, 2003, chromagenic print, 30 by 40 inches (courtesy the artist).

War

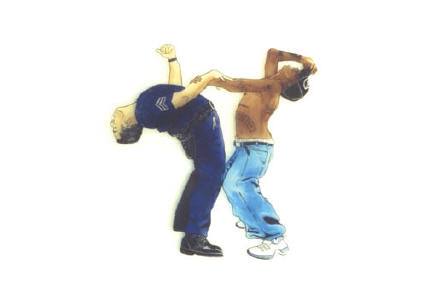

Shortly before “Cyber Arte” closed, another Los Angeles artist became embroiled in a censorship controversy. Early in 2001, the painter Alex Donis was offered a solo show at the Watts Towers Art Center, a community-based cultural center in a mostly African-American neighborhood in South Central Los Angeles. Donis was selected for the show partly because he had taught art at the Center for five years during the 1990s. The suite of paintings Donis created for the exhibit featured fictionalized pairings of Los Angeles Police Department officers dancing with members of black and Latino street gangs. Donis titled the series “War,” referring to the violent, intensely adversarial standoff that has long existed between gang youths and the LAPD.

After Donis had installed the paintings in the Art Center but prior to opening, a group called the Watts Towers Community Action Council demanded the paintings be removed and informed the art center of anonymous threats that violence (against the works on display or the center’s staff and visitors) might ensue if the works remained. The center immediately cancelled the exhibition and, without Donis’ knowledge or consent, took down his paintings.

According to Mark Greenfield, Director of the Watts Towers Art Center at the time, the right to freedom of speech guaranteed by the first amendment of the U.S. constitution did not protect Donis’ art because “this exhibition was akin to yelling ‘fire’ in a crowded theatre.” On this view, the work posed an immediate physical threat to public safety that superseded the artist’s right to free expression.

Donis’ take was, not surprisingly, quite different: “My work for many years has been to understand hatred in society and how, as an artist, to dissolve it by bridging vast social divides. This is something I thought I had succeeded at via this exhibition. Yet these pictures, these ideas, are being censored. My rights and my freedom of expression are under attack.”

What makes these pictures and ideas so offensive? According to the local press, paintings featuring members of the Crips, Bloods and other street gangs flew in the face of the affirmative, civic-minded mission of the Watts Towers Arts Center. Other justifications for removing the work argued that, because Donis—a Guatemalan-American artist living on the West Side of Los Angeles—was an outsider to Watts, his paintings were not appropriate for a community center in a predominantly African-American neighborhood.

As with Lopez’ Our Lady, the various combatants are deafeningly silent regarding the sexual content of Donis’ “War” series. Donis places each of his couples against an undifferentiated white background, suspending them outside historical context and political conflict. His dancers appear before us like lucid, Technicolor fragments from an otherwise indecipherable dream that restages their adversarial relationships marked by hatred and violence as dances of joy and mutual pleasure. He forces deep-seated animosities between men to give way, however temporarily or tongue-in-cheek, to affection.

To create these works, Donis photographed black, white and Latino gay men dancing together at discos and outdoor dance parties. In addition to these photographs, Donis also snapped shots of police officers in various L.A. neighborhoods in order to study their uniforms, badges and holstered guns, and photographed queer men and women dressed up as cops at the 2001 gay pride parade in West Hollywood.

Alex Donis, from the series “War,” Officer Moreno and Joker, 2001, oil and enamel on plexiglas, 28 by 41 inches (private collection).

Reuniting the source photographs with the paintings in the “War” series emphasizes the paintings’ delicate play of racial, sexual and sartorial fantasy. This process becomes yet more complex once we factor in the drawing process through which Donis gradually makes the transition from photography to painting. Do paintings such as Lucky Dice and Officer Gates or Shy Boy and Captain Brewer depict police officers and gang members, or gay men dressed like them? Are we viewing racially marked subjects—black and Latino street kids and white, black and Latino police sergeants and captains—or fantasmatic bodies whose race is merely a matter of artistic assignment, of choosing this or that paint color and compositional device?

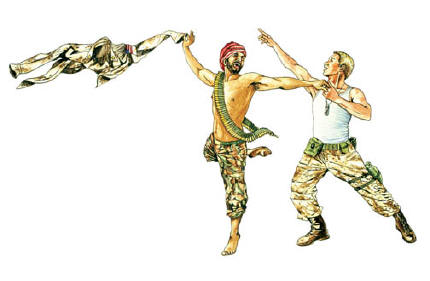

Alex Donis, from the series "Pas de deux," Abdullah & Sgt Adams, 2003, ink and gouache on board, 16 by 24 inches (collection of Richard Meyer & David Roman).

Rather than answer these questions, I want to consider the inaugural painting in a new series by the artist, which may well prove as controversial as “War.” Abdullah and Sgt. Adams from late 2003 presents a pairing that, right now, seems impossible. An American marine in dog tags and battle fatigues performs a ballet with a barefoot and shirtless Iraqi soldier in a cloth headdress, camouflage pants and a sash of automatic machine gun artillery. Abdullah strikes an arabesque position while waving his partner’s military-issue shirt in the air. The painting works, in part, by reconciling wildly divergent associations into a formal coherence. Or, to put it another way, we might say that Abdullah and Sgt. Adams relies equally on the pictures of warfare in the Middle East (Donis used an image from the Web as one of his sources for Sgt. Adams’ uniform) and on photographs of the Royal Ballet touring in 1963.

Censorship typically insists that an image’s meaning is fixed and locatable—this is “obscenity,” the censor argues, nothing more or less. As an art historian, I try to attend to the formal and symbolic nuances of controversial works of art, to how they inevitably exceed the verdicts rendered against them. But I am also interested in how censorship itself provokes responses, especially in subsequent works of art, whether by the artist under attack or by other practitioners. Censorship generates limits but also reactions to those limits; the silence it imposes provokes its own responses. When Adonis’ pictures of gang members and police officers were removed, the Watts Towers Arts Center posted a sign that said, “War is Cancelled”—which I like to think inspired Abdullah and Sgt. Adams, however indirectly or unconsciously. War is cancelled and the soldiers, no longer opposed, celebrate together. Or perhaps we should say that, could we create a space where this partnering could occur, a utopia beyond conventional notions of national, social or sexual association, that space would be war’s opposite, its cancellation.

Double Duty

While teaching photography part-time at Shelton State Community College in Tuscaloosa, Alabama in 2003, John Trobaugh was invited by his department chair to exhibit recent work at the college’s art space. Trobaugh displayed his “Double Duty” series, which depicts pairs of Ken, GI Joe and other male dolls and action figures in outdoor locations. Through a careful positioning of the dolls and some perspectival distortion, Trobaugh’s photographs integrate the action figures into much larger environments, most of which are verdant spots at the University of Alabama, thus refashioning the campus into a site of same-sex courtship and affection.

Shelton State’s president, Rick Rogers, insisted that the “Double Duty” photographs be removed. According to a written statement, Rogers objected to the show partly because it “coincided with the opening, at the college theater, of the play Arsenic and Old Lace, a family comedy.” Protest letters and unflattering articles in the Chronicle of Higher Education could not make President Rogers back down. Trobaugh observed, “If these guys had guns to each other’s heads, I guarantee you [the College President] would not have had them removed...And I bet nobody would object to that, either, because they are used to seeing men that way. That is reason in and of itself to have this exhibit.” While Trobaugh resigned from Shelton State because of this episode, Arsenic and Old Lace finished its run without further incident.

A digital collage at a folk art museum in Santa Fe; a suite of paintings at a non-profit art space in Watts; a faculty member’s photography show at a community college in Tuscaloosa—in themselves, the fights around these works may seem localized and insignificant next to the enormous impact of the Serrano and Mapplethorpe controversies in 1989, the resulting public debate over federal funding and the consequent limits of creative freedom. However, these and many other local instances of arts censorship link directly to the culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Then as now, the censorship of homoerotic imagery extends beyond specific artists or works to broader questions of social freedom and inequity.

We tend to think of the culture wars as a historical episode that, at least in terms of federal funding to the arts, is over. However, in the landmark case of Lawrence v. Texas decided in June 2003, the Supreme Court ruled that state sodomy laws were unconstitutional, thus sweeping aside this country’s longstanding criminalization of homosexuality. Angrily dissenting from the majority opinion, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote, “The Court has taken sides in the culture war, departing from its role of assuring, as neutral observer, that the democratic rules of engagement are observed. Many Americans do not want persons who openly engage in homosexual conduct as partners in their business, as scoutmasters for their children, as teachers in their children’s schools, or as boarders in their home.” In a sense, Scalia was right to point out that the decriminalization of consensual homosexuality belongs to a broader culture war over the definition and limits of citizenship, privacy, home and family, including the question of same-sex partnership and the right to marry. Conflicting beliefs about these definitions—and anxieties about what might happen when these definitions are forced to change—fueled the recent attacks on Alma Lopez, Alex Donis and John Trobaugh just as they motivated the vigorous objections to Mapplethorpe’s work in 1989.

Contemporary art sometimes asks us not only to confront the social conditions under which we live but also to imagine alternatives to those conditions, to consider a world in which a police officer might disco dance with a gang member or an Iraqi solider perform a pas de deux with an American G.I. The freedom of artists to pose such alternatives continues to be contested and curtailed, whether by the Church, the State or the prevailing beliefs of local communities and constituencies. The ability of contemporary art to generate public debate—and to provoke attempts at censorship—is a sign not of that art’s perversity or marginalization but rather of its centrality to democracy’s practice and promise.

NOTES

1. In 1531, the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared on a hill near Mexico City to Juan Diego, a poor native recently converted to Catholicism. In the centuries since that appearance, many miracles, cures and interventions have been attributed to the Virgin of Guadalupe. The Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe is celebrated with mass processions, fireworks, dancing and other festivities every December 12th.

2. Lopez’ work fits into a longer feminist Chicana tradition of reinventing the Virgin of Guadalupe in modern guises, such as Ester Hernandez’ woodblock print The Virgin of Guadalupe defending Chicano rights (1977), in which she steps out of her shell to deliver a karate kick. This work did not create a controversy like that which attended Lopez’ later collage.

3. M. Barol, “’Our Lady’ Art Unrobes Icon and Unleashes Parish Protest,” Albuquerque Tribune, March 22, 2001, A1.

RICHARD MEYER is associate professor of modern and contemporary art at the University of Southern California and author of Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art (Oxford University Press, 2002), which Beacon Press released in paperback this year. ART PAPERS LIVE! presents a lecture by Dr. Meyer this November 10 at Atlanta’s 14th Street Playhouse. This event is free and open to the public.