http://blogging.la/2005/12/12/from-tepeyac-to-east-la/#comments

From Tepeyac to East LA

December 12, 2005 at 10:02 pm in Uncategorized

Recently, I gave my brother a black t-shirt emblazoned with a white stencil of la Virgen de Guadalupe. She wasn’t the same Virgen my mom has placed throughout our home. This Virgen’s demure face was covered with a handkerchief and rather than hold her hands in prayer, she held a rifle. A ribbon below her feet showed the well-known mantra of the 1910 Mexican Revolution and 1994 Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, “Tierra y libertad!”

I warned my brother about wearing the shirt in front of our mother and grandmother. They probably wouldn’t approve, and I wonder what they would think of the dozens of artistic renditions, depiction in films and other creative interpretations. These renditions on a 474-year old image by Chicanas/os have gone on to encompass all that is Mexican, not just the religious aspect.

Yet despite her indigenous and European religious roots, she is not limited to an alcove in a church or a small altar in a home. La Virgen de Guadalupe is the subject of numerous works by scholars, writers, artists, actors and musicians. Scholars see her as symbol of the syncretization of indigenous and Catholic religious beliefs. Activists for immigrants rights, improved conditions for farmworkers, the Zapatista movement in Chiapas, and pro-life groups have used her image on banners and billboards. Franklin Avenue reported that just last month she was advocating a SÌ vote on Prop 73. No surprise there, most Catholics are pro-life and la Virgen is revered by all Mexican Catholics.

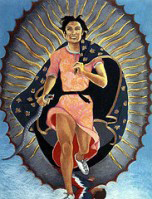

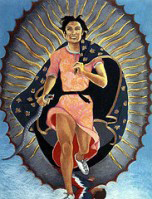

All us Guadalupanos can’t agree on how she should be interpreted or displayed. Alma Lopez’s digital piece Our Lady has been the subject of controversy, censorship and hate mail since 2001. Last year, Gustavo Arellano reported on the controversy over the piece appearing in an Orange County museum.

When the Cathedral of our Lady of the Angels opened, Guadalupanos felt that the shrine to la Virgen de Guadalupe was relegated to the “maid’s corner” of the grand cathedral. They felt that a digital reproduction would be damaged by the elements and denying her a central space was like denying the force of Mexican Catholics in the archdiocese.

Others have, in some way, protested her ubiqitousness around LA. In 1999, residents of South LA were befuddled and upset by the whitewashing and scrawling of 666 on the faces and bodies of Virgens throughout the area. Mexicans in the area believed the defacing of the Virgens could have come at the hands of Evangelicals, Satanists or shady artists who just needed more work.

It’s hard to please so many different people. Even though we celebrate la Virgen de Guadalupe collectively, we know that her meaning will differ with every Guadalupano you ask. RubÈn MartÌnez, an LA writer, calls her “the Undocumented Virgin” because she transcends the militarized border between Mexico and the US. As a student, I turn to her to find greater meaning in my roots and a connection to my family. For my grandfathers who left their homes in Zacatecas and Guanajuato to work as braceros, she served as protectress of harm in an often hostile an unknown environment. For my grandmother, she is a symbol of the strength of women. For my parents, she’s a part of the country they left as children to be with their families in el Norte.

For other Mexicans in and around LA, she “symbolizes the entire coherence of Mexico, body and soul.”

Image: Portrait of the Artist as Virgen de Guadalupe, by Yolanda Lopez, 1978

Quote: Richard Rodriguez in an essay in In Goddess of the Americas: Writings on the Virgin of Guadalupe (edited by Ana Castillo). This book is a great resource for more on la Virgen de Guadalupe.