http://www.tikkun.org/article.php/july2010perez

Decolonizing Sexuality and Spirituality in Chicana Feminist and Queer Art

by Laura E. Pérez

In academic and art world spheres, particularly in the studied nihilism of much postmodern art and poststructuralist thought, the spiritual and the political largely remain separated, following assumptions dating to the Enlightenment in the modern Western world -- a binary that is clearly one of the last ‘‘frontiers’’ to be deconstructed.

During the last four decades, however, a number of Chicana feminist and queer artists have challenged this division, invoking the spiritual for political effects that are very different from those sought by racist, sexist, homophobic, fundamentalist politicians and religious leaders. Instead, their art calls attention to the politics of the spiritual, that is, to the fact that spiritual beliefs and practices -- however varied these may be -- generate social and political effects that matter.

Critical of notions of family, gender, and sexuality imposed by patriarchal and heteronormative Eurocentric Christian colonialism, these Chicana artists have embarked on a search for more egalitarian social, political, and spiritual models that help undo or heal mind-body-spirit binaries. In some cases following a do-it-yourself cut and paste approach to spirituality and in others, reclaiming non-western spiritualities ancestral to them, they have variously assimilated goddess-spiritualities (whether of bona fide or recent vintage) from around the globe, Eastern spiritualities, African-diaspora santería, Jewish mysticism, and Native American spiritualities of Mesoamerica and North America.

A culturally hybrid spirituality is what most often is cited or articulated in the work of these artists. This hybrid spirituality is a ‘‘politicizing spirituality,’’ as artist Amalia Mesa-Bains phrased it, and it emphasizes embodiment -- that is, manifestation on the earthly plane in acts of goodness with respect to real bodies and in human societies, in nature, and on the globe, rather than in vague, abstract, and binary notions of goodness, God/gods, s/Spirit(s), and spirituality. What is explored, articulated, or deployed by their art is a notion of spirituality whose effects matter socially and politically. In the work of these women, it is the day-to-day practices of spiritual consciousness and its material effects on as well as in our bodies, as well as in society, rather than identification with the dogma and ritual practices of religious organizations, that are brought to our attention as mattering individually, socially, and globally.

This body of art, mindful of culturally and historically different notions of art, spirituality, gender, and sexuality, offers a critical investigation into their relations. In some work, the inquiry is centered on how religious beliefs about sexuality and gender buttress male privilege in society and religious institutions. In more recent work, this concern is extended into the sex-work industry through both religious and popular cultural visual languages. Other work traces heterosexist privilege in nationalist discourses and the religious ideologies used to sustain these. Still other pieces are concerned with the ambiguous zone between sexually and spiritually liminal beliefs and behavior.

“Making Face, Making Heart”

In ixtli in yollotl is a trope, a difrasismo (diphrasm), that yokes together the Nahua concept of ‘‘face’’ to that of ‘‘divinized heart,’’ to express personhood as the attunement between inner and outer being, the person and the community, the earthly and the divine. Life is the process of aligning these and properly making for one’s self the face and heart of a harmonious, spiritually guided person of higher purpose. In Nahua thought, this work of alignment is particularly the work of artists. For negatively racialized women, for women further shamed because of their sexuality and sexual preferences, for those made lowly by unjust inequities, ‘‘making face, making heart’’ involves a labor of deconstruction and reconstruction, of tracing the histories of meaning attached to the verbal and visual images in which we daily traffic, of questioning the provenance of habits that push us back into place whenever we trespass social expectation. It means tailoring the fit of our thought, visuality (what and how we are able to perceive visually), and daily social performances of being to our particular bodies, as Gloria Anzaldúa so vividly suggested in the preface to her anthology Making Face, Making Soul:

Women of color strip off the máscaras [masks] others have imposed on us, see through the disguises we hide behind and drop our personas so that we may become subjects in our own discourses. We rip out the stitches, expose the multi-layered ‘‘inner faces,’’ attempting to confront and oust the internalized oppression embedded in them, and remake anew both inner and outer faces. . . . You are the shaper of your flesh as well as your soul. According to the ancient [N]ahuas, one was put on earth to create one’s ‘‘face’’ (body) and ‘‘heart’’ (soul). . . . In our self-reflexivity and in our active participation with the issues that confront us, whether it be through writing, front-line activism, or individual self-development, we are also uncovering our inter-faces, the very spaces and places where our multiple-surfaced, colored, racially gendered bodies intersect and interconnect.

In other words, “making face, making heart” means blowing the stereotypes of expected behaviors we know don’t fit us.

Christian Virgins, Goddesses, and Superheroines

The courage to fashion the faces of, and the work of denaturalizing gendered and sexed expectations of, negatively racialized women is at the heart of the enormous body of Virgin of Guadalupe art by Chicana feminist artists. This art disputes the disempowering patriarchal interpretations of the Mother of God that have turned her into a model of female acquiescence to male-centered society.

Chicana artists have been at work since the early 1970s reinterpreting this image in the Mexican American community and in the larger, feminist art-making community. Through hybridization with goddesses and popular culture superheroines, they have provided a different interpretation of not only the Mexican Mary but more generally of the Christian Mother of God archetype used so unremittingly as a screen of projections for the human patriarchal imagination for more than two thousand years. In Chicana visual art, creative writing, and theater, the Virgin becomes an archetype of the powerful and empowering in everyday women, who embrace the negatively racialized female body in ways that claim it too as a temple of the sacred. These images consciously overturn patriarchal projections re-rooted in colonial sexual violence against Indigenous women and women of African origin and the characterization of the dark female body of the poor as the site of evil.

Chicana scholars and artists have dared to go beyond the merely mortal, male-centered religious interpretations of gender, sexuality, and the demonization of paganism of the non-Western ‘‘dark races,’’ refashioning for themselves interpretations of Guadalupe, the goddesses of Nahua, and other non-Christian pantheons that no longer cost them, or other women, a pound of flesh. Whether as culturally familiar symbol or spiritual force, they see her -- or want to see her, as Sandra Cisneros has written -- as a figure of empowerment for women, a champion of the poor and of social justice, their champion, instead of patriarchy’s yes man. ‘‘My Virgen de Guadalupe is not the mother of God,’’ Cisneros has written.

She is God. She is a face for a god without a face, an indígena for a god without ethnicity, a female deity for a god who is genderless, but I also understand that for her to approach me, for me to finally open the door and accept her, she had to be a woman like me. . . . When I see la Virgen de Guadalupe I want to lift her dress as I did my dolls’ and look to see if she comes with chones, and does her panocha look like mine, and does she have dark nipples too? Yes, I am certain she does. She is not neuter like Barbie. She gave birth. She has a womb. Blessed art thou and blessed is the fruit of thy womb . . . Blessed art thou, Lupe, and, therefore, blessed am I. (1996, 50–51)

Chicana artists have called upon the Christian Mother of God’s Mexican -- that is, culturally and religiously hybrid -- apparition image and activated it, so to speak, as the protector of those disenfranchised by virtue of their gender, sexual orientation, stigmatizing racialization, and poverty. For in this human war of images of the divine and religious systems, and of the ideologies that make these intelligible, they recognized that women have been made lowly by the stories, visual and otherwise, that have rationalized the physical, psychological, social, economic, legal, and spiritual violence against them in male-centered cultures, beginning in the home and religious institutions. La Llorona, the weeping woman; Malintzen Tenepal, Cortés’s translator given to him as ‘‘gift’’; the curandera figure, a physical and spiritual healer; the pre-Columbian goddesses Coatlicue, Tonantzin, Coyolxauhqui, Mayahuel, Cihuacoatl -- these and other symbols, alongside the Virgin of Guadalupe, have been reimagined by Chicanas in crucial post-1965 struggles over the social, ideological imaginary that shapes, and sometimes distorts, our realities.

In Mexico, the Mother of God appeared as the Virgin of Guadalupe. Dark-fleshed, she spoke in Nahuatl to the Mexica man Juan Diego in 1531, only ten years after the Spanish seized power. Likewise, she ‘‘appears’’ to Chicana feminist artists who work with her image and that of negatively racialized women, most significantly, even through their sexualities. The nonjudgmental aspect of the Holy Mother they have invoked through their artwork accepts women whole and unconditionally, lovingly sheltering under her mantle their hard-won and decolonizing love of their own bodies and those of other women. If our sexuality, and our genitalia specifically, have been eroticized through the projection of titillating evil upon them by Western patriarchal and heteronormative culture as the gateways to a deadly carnality and sin, then by necessity the uncovering of the dignity of each and every body that Mother Mary’s and Jesus’s incarnations symbolize must contest rather the ‘‘sin’’ in demeaning representations of these, and perhaps even the idealist belittlement of and violence against a body that is unavoidably the temple of embodied being.

In Cherríe Moraga’s play Giving Up the Ghost, Marisa, raped as a child and haunted by the sexism and homophobia of culture and her own internalization of these, remembers her female lover saying to her, ‘‘You make love to me like worship.’’ She thinks of how she would have like to have responded ‘‘Sí, la mujer es mi religion’’ (Yes, woman is my religion), musing sadly in this closing monologue, ‘‘If only sex coulda saved us’’ (1994, 34). Moraga is perhaps suggesting that the healing power of lovemaking that places female pleasure and fulfillment at its center is like religion in that it aspires to be an embodiment of the spiritual ideal of love.

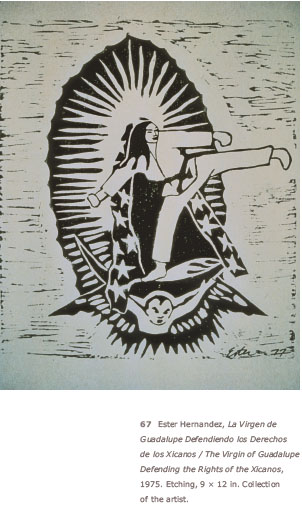

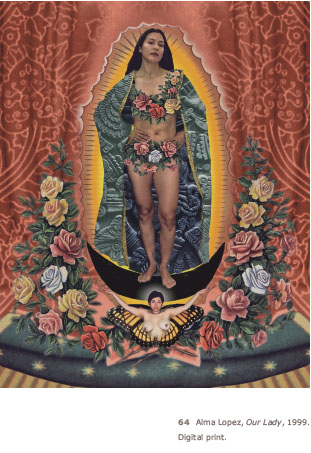

Chicana artists and the institutions that support them have repeatedly been reminded that reinterpreting the meaning and image of the Virgin as ordinary woman or goddess is dangerous work. Hernandez’s 1975 The Virgin of Guadalupe Defending the Rights of Xicanos was received negatively by some (Quirarte 1992, 21). In 1978, as a result of featuring Yolanda López’s The Virgin of Guadalupe Goes for a Walk on its cover, in heels and a dress that exposed the Virgin’s calves, the office of the feminist magazine fem received a bomb threat in Mexico City. In the late 1980s, Ester Hernandez received a death threat by phone in response to her silk-screen image La Ofrenda, which had appeared on the cover of the first edition of the anthology Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About (Trujillo 1991). More recently, Chicano nationalist activists and Roman Catholic clergy demanded the removal of Alma Lopez’s Our Lady (1999), a digital print exhibited in 2000, from the Cyber Arte show at the New Mexico International Museum of Folk Art in Santa Fe, because the artist had placed a defiant-looking woman clad in flowers within a mandorla and had bared the breasts of an equally unamused female cherub.

In the artist’s written response to the letters and demands she and the museum received, Lopez astutely wondered what it is about women’s nude bodies that seems inappropriate and sacrilegious to the men leading the protest to censor her image. The historical and present-day hypervisibility of images of women in positions of subservience and as objects of male power, sexual desire, and violence, cyclically reinforce, and are reinforced by, the use of the Virgin of Guadalupe as a model of abnegation and passivity with respect to patriarchy. Thus, Chicana feminist artists struggle over the representation of the everyday negatively racialized female body through her. Her mandorla, her gown, and other signs of her sanctity are borrowed visually to conceptually ‘‘protect’’ or dignify and sacralize the otherwise trampled bodies of real women. As patroness of the Chicana/o movement, and the symbol of the righteousness of other radical struggles for social justice, the Virgin has been promoted to goddess, queen, and super-heroine by the Chicana feminist movement.

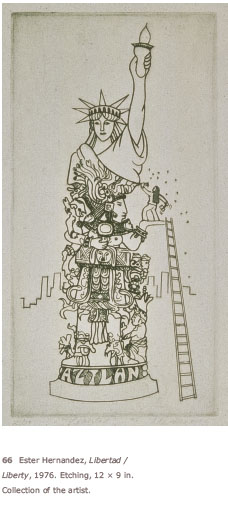

One early image combining the popular cultural with the Mesoamerican was produced by the San Francisco-based artist Ester Hernandez, Libertad or ‘‘Liberty,’’ a 1975 etching. It depicted a female artist chiseling away at the Statue of Liberty, freeing from within it a regal Mayan female figure and, in the process, creating a culturally composite image of Lady Liberty that encompassed women of color, descending from Indigenous and mixed bloodlines, alongside those of European descent.

One year later, Hernandez created The Virgin of Guadalupe Defending the Rights of Xicanos, using the familiar iconography of the Virgin’s mandorla, or full body halo, to suggest an idea of feminine power and sanctity that differs from the one received through male-centered interpretations of a Bible-mandated female subservience to men (see image at very top of this article).

Early Chicana feminist scholars such as Adelaida Del Castillo, in her 1974 analysis (reprinted in Del Castillo 1990) of the misogynistic demonization in Mexican nationalist thought of the Indigenous Malintzen (‘‘La Malinche’’) as the traitor of mestizo Mexico, and the historian Anna NietoGomez, in her essays of 1976 and 1977, showed the links between imperialism, racism, patriarchy, and marianismo, or male-serving Marianism. NietoGomez argued that the ideology of marianismo rationalized the Christian European colonizer’s patriarchal, racialized gendering of women, such that after the Spanish invasion and colonization, more socially mobile and empowered Native American women inevitably played the fallen Eve to the more socially controlled, American-born criollas (Spanish) and white-identified mestiza women (NietoGomez 1976, 1995, reprinted in A. García 1997). Del Castillo and NietoGomez wrote in response to male-centered Chicano nationalist criticism of Chicana feminism as disloyal, ‘‘white,’’ ‘‘lesbian,’’ and altogether unnatural to Chicano culture.

The excavation among Chicana artists in search of knowledge of ancestral female pre-Columbian cultures, particularly when juxtaposed to their Guadalupe-themed work, was far from being a naive idealization of the good old days before colonization. Feminists did not picture themselves as the swooning Ixtacihuatl princess in the arms of Popocatepetl, according to the legend immortalized in calendars distributed each new year by butchers, grocers, and barbers in Spanish-speaking neighborhoods in the United States. If, as I have said, much Chicana feminist art using the Virgin’s image shows her as an everyday female -- countercultural urban punk, working-class middle-aged laborer, physically disabled, spunky, spirited, defiant girl, agent of sexual desire both straight and queer -- another body of Chicana art represents her as a goddess. And how could it not be so, when research revealed the presence of gender-bending creator gods, expressed simultaneously as female and male (such as Ometeotl), and pantheons of similarly twinned gods representing the cosmos and nature? Feminist scholarship disseminated by Gloria Anzaldúa and others also revealed that the Mexica (‘‘Aztec’’), though less thoroughly than Western culture, had displaced female power in their elevation of the male god of war Huitzilopochtli over and above his sister Coyolxauhqui. The Virgin of Guadalupe and pre-Columbian goddess myths and images thus served to inspire Chicana feminist scholars and artists to investigate, and then visualize, nonpatriarchal notions of womanhood as modeled by deity figures. The juxtaposition of the visual traditions of both popular Mexican and Indigenous cultures present in the dark Virgin, ‘‘La Morenita,’’ has long been observed, but it was further explored in experiments combining visual elements from various European and pre-Columbian traditions.

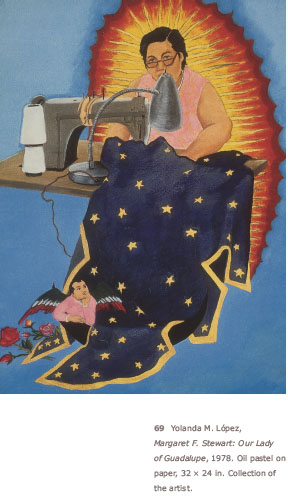

Yolanda López experimented with these and other cultural collages extensively in her Guadalupe work from 1978 through 1988. Her well-known oil pastel Guadalupe triptych of 1978, has been reproduced numerous times, mainly in feminist and Chicana/o art publications.

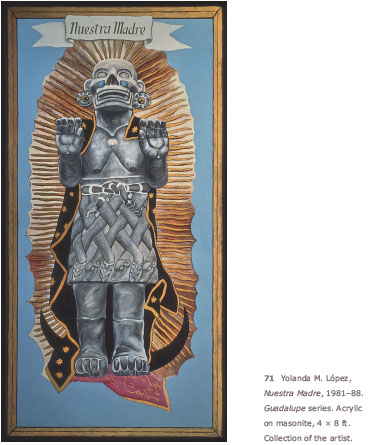

These drawings were part of a larger, groundbreaking Guadalupe series exploring the possibilities of mixing European and Mexican-Indigenous art histories and visual art languages. At the time López was an atheist; her concern with Virgin of Guadalupe iconography was more an experiment of speaking through the familiar to a population visually and not simply religiously shaped through culturally omnipresent images (López 1996). López made collages of Indigenous breast-feeding women, such as Madre Mestiza (1978) and Eclipse (1981), the latter of which showed an image of the artist herself jogging away from the frame. She created composite images of the Virgin and an earlier Nahua female goddess, a version of the creator-destroyer goddess Coatlicue, in Nuestra Madre (1981–88).

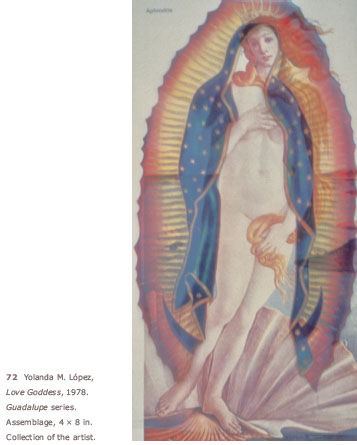

And in Love Goddess (1978), she overlaid Botticelli’s Birth of Venus carefully within the Virgin’s mandorla, suggesting that despite different traditions, these two images represent continuity in the discourses of gender and sexual desire within male-centered cultures, even as these were signified by the clothing of one and the lack of it in the other

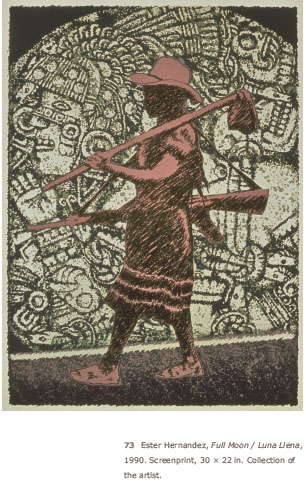

This melding of the visual languages of sanctity in the Western religious imagination, the popular, and the Native American continued in the work of many Chicana artists in various media, including the later work of Ester Hernandez. In Full Moon/Luna Llena (1990), created during a period of active, if covert, U.S. intervention in the civil wars of Central America, Hernandez protectively enveloped a Central American Indigenous campesina revolutionary within the shadow of the moon goddess Coyolxauhqui.

Alongside other Chicana feminist reinterpretations of the Mexica myth, Coyolxauhqui, the daughter of creator-destroyer goddess Coatlicue, is no longer characterized as evil. Rather than being the vengeful daughter wishing to destroy her mother because she was mysteriously impregnated by downy feathers while sweeping, she instead attempts to destroy her brother, the god of war who would become the Mexica’s supreme deity, Huitzilopochtli, throwing off balance the earlier, broader Nahua culture’s notion of male-female balanced deities (León-Portilla 1963, 30). Here, it is the aspect of the righteous warrior woman that we saw in Hernandez’s early karate-kicking Virgin that is invoked through Coyolxauhqui’s image, reminding us of a lineage of female warriors that is interestingly not incompatible with the tradition of Mary as the quintessential warrior against evil, whether in the spiritual realms or as it manifests on earth through human acquiescence.

In Juan Soldado, Alma Lopez replaced both mandorla and Virgin with the popular saint and patron of the wrongfully accused, Juan Soldado (‘‘Soldier John’’), one of many ‘‘victim-intercessors’’ or popular saints wrongfully accused to whom Mexican American populations, immigrant border-crossers in particular, appeal.

Isis Rodriguez, a Chicana Puerto Rican artist originally from Kansas and now based in San Francisco, cast the Virgin of Guadalupe in a Virgin series that includes girl bikers, a stripper, a brown Superwoman and Little Miss Attitude, in numerous cartoon superheroine images. In this tradition of fictional visual superheroines crossed with the Virgin, she followed the pioneering Yolanda López in her 1978 Tableau Vivant. Rodriguez, like Alma Lopez and Yolanda López, emphasized the Virgin’s superhuman ability to crush evil, as does Laura Molina’s superheroine, Cihualyaomiquiz, the Jaguar woman, helping us to identify evil in everyday yet powerful ills.

The rediscovery, reclamation, and reimagining of Nahua, Maya, and other goddesses among Chicana feminist artists has often happened along side Virgin of Gualdalupe images or in composites of these as archetypes of spiritual, embodied power for women. Gloria Anzaldúa’s writing in this regard, in Borderlands/La Frontera. The New Mestiza (1987), was probably the most influential. Irene Perez gave visual form to this feminist effort to revive the goddesses from patriarchal demotions in her 1993 rendition of the once-dismembered warrior daughter, Coyolxauhqui. Like Santa Barraza, Perez painted her emerging from the maguey plant, symbol of life and regeneration, whole, open-eyed, and in motion.

In her later rendition of Coyolxauhqui on one of the two walls of the Women’s Building in San Francisco as a part of the Maestrapeace mural, co-created with a team of six other women and many volunteers, Perez painted the goddess two stories high and breaking out of the moon disc to which she had been confined in myth and in pre-Columbian sculpture. In both versions of the image, the artist drew her with an exposed Sacred Heart, encircled with thorns and crowned with flames. The visually and spiritually hybrid Marian imagery that we have seen -- a mere fraction of what exists -- is a decolonizing visual gallery of the socially wronged who are pure of heart.

The work of these Chicana artists expresses humane, rich, and complex understandings of socially significant, spiritually embodied being. In it, the dark, the female, the queer body is also sacred, as a creator and creative force, a goddess or superheroine force being summoned in the battle against dehumanizing religiosities, social mores, and ideologies of the body and sexuality that are man-made rather than divine or natural and that are harmful rather than healing. Their spiritually hybrid works embrace gender, sexual, and cultural difference as a natural and interrelated diversity, and circulate alternative, more socially democratic visions of respectful coexistence in the United States. Indeed, Chicana feminist and queer artists display the courage to attempt to inspire or provoke greater balance between who we appear to be (‘‘face’’) and who we long to be (‘‘heart’’). They teach us to perceive and imagine differently, and that seeing is a learned, revealed, ever-changing, and transformative process, whether we do so through the mind, the eyes, the heart, or the spirit. If we are receptive, their work contributes toward leading us to beliefs and practices of greater personal and social integrity and therefore harmony.

These works ultimately remind us that we are inescapably, in visible and invisible ways, each other’s other selves, an idea expressed in the Mayan In’Laketch. It is my hope that Chicana art may contribute to a greater and more healing understanding of ourselves and each other, and that we may be spurred along on the great spiritual, social, political, and artistic adventure of more fully realizing our best selves, societies, and globe as a part of the interconnected web of life into a future that will succeed us, and for which we too are responsible.

Laura E. Pérez is associate professor in the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. This article was adapted from the sixth chapter and conclusion of her book Chicana Art: The Politics of Spiritual and Aesthetic Altarities (Duke University, 2007), a part of the Objects/Histories series edited by Nicholas Thomas.