https://wendycarrillo.wordpress.com/2010/12/15/el-dia-de-la-virgen-de-guadalupe-a-reflection/

Wendy Carrillo's Blog

El Dia de la Virgen de Guadalupe: A Reflection

From my post on The Huffington Post

Every year on December 12, Catholic Latinos throughout the world celebrate El Dia de la Virgen de Guadalupe, the glorious day that our Lady of Guadalupe appeared to Juan Diego. In Los Angeles, this celebration is one of the largest in the nation.

For many, celebrating this day is not just a religious obligation, but a gift that far surpasses the space and time of church walls.

As I began my journey in understanding the complexity of her image, her deafening silent absence from the Bible and the wild popularity that surrounds her, I began to see that the Virgen was more than just a religious symbol; she was, and continues to be, a transformative figure for women, representing far more than the established laws within Catholicism.

My earliest memories are of a Virgin Mary on store sides, brightly spraypainted or tiled over otherwise beige or tagged walls in my community of East Los Angeles.

I romanticize her imagine because when I first met her, she was the Virgin mother – sacred and special. She was the mother of Jesus Christ, the guy on the cross at the altar who died for our sins. The obvious implications of Catholic guilt were well-established.

While in college, I rediscovered the ancient truths of my ancestors in a Chicano Studies course and I realized that the Virgin Mary was not just a Catholic apparition, but that she was the in fact, the Brown Aztec Goddess, Tonatzin. For the first time, I saw the Virgin as a woman, and as a woman of color.

Sandra Cisneros, who wrote more than just A House on Mango Street, put it best: “She is Guadalupe the sex goddess, a goddess who makes me feel good about my sexual power, my sexual energy.”

I gasped when I read how Cisneros wrote about women and women’s sexuality. She had sexualized La Virgen like no other and when I looked at her statue in my church, I gasped again when I saw for the first time that she had no breasts.

How could I have missed such an obvious fact?

This wild and confused time of my early twenties was rather exhausting as I re-learned and questioned my faith, my religion, and my loyalty to the church. I was coming into my own as a young woman and rejected much of the church’s traditional beliefs towards women and women behavior.

Cisneros had lit a fire.

Instead of becoming a born-again Christian, I became a born-again Aztec princess, ready and willing to fight for Aztlan and change my name to something much more exotic than Wendy, something more along the lines of Xotchil or Citlatli. The names of my ancestors and the women of my past.

I wanted to be a walking weapon of knowledge ready and willing to detract my foes, a Chicana feminist, a super heroine, armed with fancy words like hegemony, misogyny, patriarchy, and riddled with anecdotes of the colonization and oppression of my people.

I was one pissed-off chick.

However, I found an unsettling sense of peace through Cisneros. I was uplifted and aroused by her prose. In “Guadalupe Sex Goddess,” Cisneros shockingly and explicitly compared her panocha to the Virgen’s.

“I want to lift up her dress as I did my dolls, and look to see if she comes with chones, and does her panocha look like mine, and does she have dark nipples too?”

What was I suppose to make of that? Was this something I could share with my mother?

Being the rebel rouser that I was, I did.

“No me gusta, es muy vulgar”, my mother said to me. (“I don’t like it, it’s too vulgar.”)

My grandmother, a woman who is three times divorced, chimed in, “Come se atreve! Santo Dios! Ay no! ay no!” (“How dare she! Good lord! Oh no! oh no!”)

My mother, an immigrant from El Salvador and a current college student, is an elementary school teacher. She considers herself “an independent thinker, but culturally modest.”

Mostly, she makes up her own rules.

My abuelita comes from a generation where Latin prayers were the norm and when priests still faced the altar, not the people. She attends church most holidays and out “of respect.”

For many years, on the wall over my mother’s kitchen table was a painting on cloth of “The Last Supper” that she bought in 1984.

There is a figure that looks like a woman next to Jesus. Mary Magdalene perhaps?

My mother thinks it’s one of the apostles, regardless of the fact that she clearly has breasts, and what looks to be an Adam’s apple.

I had never really put much thought or attention to this painting, but I often wonder about it now.

To me she is ambiguous, transgendered, and desexed. She, like the Virgin, is not given a real space to fully be a woman.

When I first read Cisneros, I was mortified and insulted. My Latina consciousness befuddled with Catholic guilt could not compute.

Who was Cisneros to write about La Virgencita like that?! Patron of liquor store walls?

Bewildered by my own awakening, I sought to understand the concept of “women” through writing, especially woman of color.

I discovered Gloria Anzaldua, who guided me through my mestiza awakening.

“Because I am in all cultures at the same time, I am confused by the voices that speak to me.”

As a mestiza woman, I could identity with my indigenous past, a past before colonization and Catholic guilt. I began to understand why I was enamored with the idea of the Virgen as a woman and not simply a symbol of religious faith.

As Anzaldua wrote, “the new mestiza learns to be Indian in Mexican culture, to be Mexican from an Anglo point of view.”

I was breaking down the subject-object duality that was keeping me a prisoner in my own consciousness.

Yet, I was still engulfed with a national identity that surpassed Mexican borders.

Besides having to identify myself within the women’s world of white women and women of color, how could I identify with a “Mexican” identity when I was not Mexican?

I am a Salvadoran born Latina from East Los Angeles. I am Chicana by default, Mexican by acculturation, Salvadoran by birth, and an American citizen (by naturalization) for voting purposes.

I am the daughter of an educated Latina, who once cleaned homes for a living in the US, and the granddaughter of a former nurse who helped wounded soldiers in a civil war back home.

These identities shape my thinking as a woman, and I wonder, did La Virgen ever think the way I think?

Did she ponder the notion she was saintly mother, whose son would die at the cross for mankind? Did she in her apparitions to Juan Diego imagine herself as indigenous and godly? Did she in the words of Aretha Franklin, feel like a woman?

Patricia Collins, a feminist author, wrote about a concept called “the outsider within,” which helped illustrate the notion of experiencing and living through various layers, all of which intersect with one another: “whether the differences in power stemmed from hierarchies of race or class, or gender or… the interaction of all three, the social location on being on the edge matter(s).”

So here I found myself attempting to understand the complexity of La Virgen.

On one point, I wanted to be like my Chicana counterparts who believed the Virgen was a sexual creature. She desired and was desired. She didn’t remain a virgin, she married, had children and had to have been, by all accounts, a sexual being.

Yet, on another point, her complexity as a saint, and the mother of our Lord haunted me.

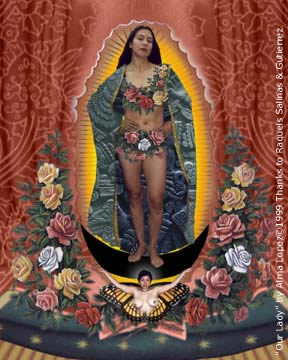

I showed my mother the image of La Virgen as depicted by artist Alma Lopez.

Artist Alma Lopez' Rendition of Our Lady of Guadalupe

She scowled immediately and said, “is nothing sacred anymore?”

At first glance, the semi-nude woman, adorned by roses throughout her private areas is shocking. A green cloak with Aztec symbols graces her shoulders, her hands rest her hips in defiance, her brown hair long and loose, she stands on top of black crescent moon held by a topless female with butterfly wings.

Lopez’ interpretation of La Virgen was inspired by Cisneros’ writing.

This is not the image the Catholic Church has of the Virgen Mother nor the imagine that is widely distributed amongst the devout.

But it is, nonetheless, an image that exists amongst circles of Chicanas who like Cisneros have found themselves as women through a new interpretation of La Virgen.

In 2009, I wandered the plaza of Our Lady of Angels Cathedral in Downtown Los Angeles on El Dia de la Virgen. I looked around and saw Latino men, women and children celebrating her — some dressed in the traditional robes of Indigenous people, Aztec dancers, wearing elaborate feather headdresses, burning sage and incense, others as indigenous representations of people from Oaxaca.

They traveled from East Los Angeles to the marbled floors of the new church, where one of the reprinted versions of Juan Diego’s tilma was displayed at the altar.

This church, a world away from East Los Angeles was isolated and cold.

A few blocks down the road, La Placita Olvera, the oldest church in Los Angeles, was alive and festive.

On a church side wall, a rendition of the Virgen with Juan Diego at her feet is painted on tile. The wall was adorned with hundred of roses brought my visitors.

It is here they pay homage.

I realized it’s not the sanctity of her image that is prayed over.

She is respected and loved in various ways.

To some, she represents the divinity of our mothers, and the virtue of our gender.

To others, she represents womanhood, and power over oppression.

To me, she represents an idea. A faith based icon of womanhood that binds, contradicts, and explores intersectionality at its core.

To look upon her image is to look inside every woman before me and from my past.

She is the mother goddess, Tonatzin, wearing a different mask, still imploring me to think that duality exists within us and that regardless of religious affiliations, she is within grasp.

Celebrating her is the celebration of mankind, the celebration of womanhood and the celebration of the divine that exists within.

In the roses, she comes to life.

* Original post incorrectly mentioned Dec. 12 as Our Lady of Guadalupe’s birthday. Correction has been made by author. *